Sat 16 May 2009

Proving that Denial isn’t just a river in Egypt, only 25% of pre-retirees are considering postponing their retirement age despite being woefully underprepared financially for retirement.

From a McKinsey Quarterly Economic Study:

Although consumers have taken some … steps, these could be masking a deeper failure to understand the state of retirement security. McKinsey?s retirement readiness index (RRI)?which uses Social Security, defined benefits, defined contributions, and other financial assets to measure the financial preparedness of households for retirement?is currently at 63 for an average household in January 2009. Consumers must have an RRI of 100 to maintain their current standard of living at retirement. An RRI below 80 calls for large reductions in spending on basic needs, such as housing, food, and health care.

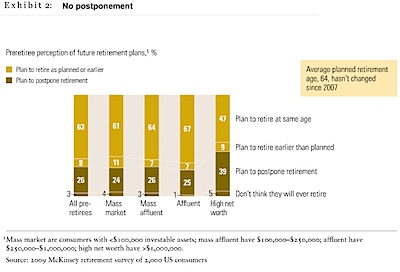

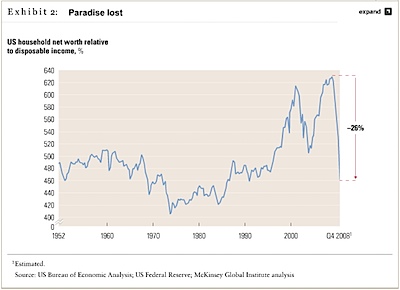

Yet our survey showed that only about a quarter of US consumers are considering postponing retirement as a result of the crisis: the expected retirement age, 64, hasn?t changed since 2007 (Exhibit 2). Despite the fall in home values, the proportion of people planning to finance their retirement through home equity has increased slightly.

What is the prevailing attitude and what did these pre-retirees do about it?

…consumer anxiety about interest rate risks and a lack of guaranteed income has more than doubled, to around 60 percent, from the levels prevailing three to five years ago; worries about market and inflationary pressures have jumped by half, to about 75 percent…

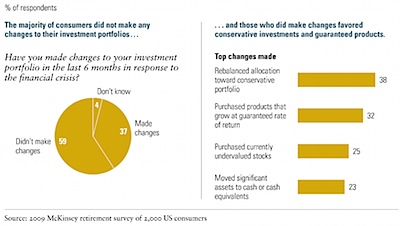

…in the past six months, only 1 percent have moved assets away from their primary financial institution, just 37 percent have changed their investment portfolios, and no more than 20 percent have changed their retirement portfolios. Those who did make changes have tried to reduce their risk levels by rebalancing allocations toward conservative assets (38 percent), products with guaranteed rates of return (32 percent), and holdings of cash and cash equivalents (23 percent) (Exhibit 1). Most preretirees have also responded to the financial crisis by curbing their lifestyles: some 60 percent reduced spending in the six months leading up to January 2009, and 73 percent paid down debt.

A separate nugget of blame from the same article:

…just 1 percent of preretirees hold their individual advisers primarily responsible for the impact of the crisis on them, compared with 43 percent who blame the government and regulators, and 27 percent who blame financial institutions.

I wonder who or what the other 30% blame?