I found Kevin Depew’s 5 Things article from Monday (at Minyanville) to have an excellent summation of what a credit crunch is, and why it is important. Here are several excerpts that can act as a primer to anyone wondering what is going on…

1. What is a “Credit Crunch”?

The simple answer is that a “credit crunch” is a general decline in the the supply of, and demand for, credit.

[A] “credit crunch” occurs when banks become more risk averse – less willing to lend – even though interest rates may remain the same, and in extreme cases, even though interest rates may go lower.

2. Why does credit growth matter in the first place?

Because in our [economic] system, economic growth is dependent upon credit expansion.

As long as credit expansion and demand for credit continues at an accelerating pace, the appearance of prosperity continues as asset prices increase. The “accelerating pace” aspect is critical. It is the key to maintaining the boom.

As Michael Darda, chief economist for MKM Partners told the Times today, ?Access to capital and credit is essential to growth. If that access is restrained or blocked, the economic system takes a hit.?

3. What do we mean by “credit expansion,” anyway?

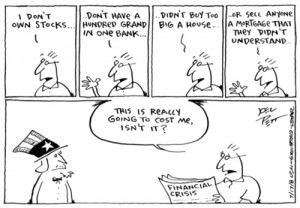

[For almost 20 years, banks lent money] at artificially low interest rates and, later, to borrowers with increasingly low credit quality. By offering willing borrowers money at artificially low rates, this encouraged [taking on more risk and] risk tolerances were widened.

This is how debt was pyramided to such an extent that one small setback, in subprime borrowing for example, resulted in such a widespread problem, problems which quickly spread to other, supposedly safe credit risks.

By offering willing borrowers money at artificially low rates, this encouraged increased time preferences among economic actors, which is to say that investment horizons were lengthened and risk tolerances were widened. This money was then overinvested and misallocated by investors in dot.com ventures and houses.

4. How, then, did we transition from credit expansion to a “Credit Crunch”?

This loss of capital creates risk aversion; lenders suddenly find they are not being repaid, say, by subprime borrowers who are defaulting on their mortgages. These lenders in turn – remember this is a fractional banking system – find that because they used the repayment of these loans as collateral for loans they took out to “malinvest,” suddenly discover they are unable to repay some of their debts. The lender’s lender is in the same boat, as is the lender’s lender’s lender.

So, what do these lenders do? They “de-lever.” In other words, they sell whatever they can – whatever is still liquid (say, U.S. stocks, for example) in order to raise capital to repay loans.

Lenders in many cases cannot, or are no longer willing to, extend credit … for they fear not being repaid.

I have heavily excerpted/edited the original article for content and clarity… see the original if you want it all in the author’s original context.

Additionally, I left off #5, which attempts to answer the question of “What Next?” Depew has a very interesting answer that is very optimistic in its pessimism… Quite entertaining.